Wyoming State Water Plan

Wyoming State Water Plan

Wyoming Water Development Office

6920 Yellowtail Rd

Cheyenne, WY 82002

Phone: 307-777-7626

Wyoming Water Development Office

6920 Yellowtail Rd

Cheyenne, WY 82002

Phone: 307-777-7626

As with all chapters in this final plan report, explicit lists of references are not provided. Instead, all references to report, documents, maps, and personal communications are maintained in the Technical Memoranda that were prepared during the current planning process. Should the reader desire to review a complete list of references for the information presented in this chapter, the following memoranda should be consulted:

The Green River Basin Water Planning Process document is one of two basin water plans compiled under initial efforts of the Wyoming Water Development Commission. Authorized by the Wyoming Legislature in 1999, the planning process' first task is the preparation of plans for the Green and Bear River Basins in Wyoming. Subsequent years will see plans developed for the northeast part of the State (Tongue, Powder, Belle Fourche, Cheyenne, and Niobrara Rivers), Big Horn/Wind, Snake/Salt, and Platte River Basins. It is the express desire of the program to revisit and update the basin planning documents every five years or so.

As authorized by the Wyoming Water Development Commission in its contract scope of work, this planning document presents current and proposed (estimated) future uses of water in Wyoming's Green River Basin. Uses to be inventoried include agricultural, municipal, industrial, environmental, and recreation. Both surface and ground water uses, as well as overall water quality are described. Given current uses, the availability of surface and ground water to meet future requirements is estimated. To lay the groundwork for future water development, a review of the current institutional and legal framework facing such projects is presented. Finally, thoughts are given to guide implementation of the water planning process.

The structure of this final report is to present findings in enough detail to explain the overall plan without deluging the reader in technical minutiae. Technical memoranda have been prepared which delve into the many individual topics in detail, and it is to these documents the reader should turn for answers to questions about details, methods, and for selected references. No separate list of citations is provided herein other than for the Technical Memoranda (which, individually, contain complete bibliographies).

Location

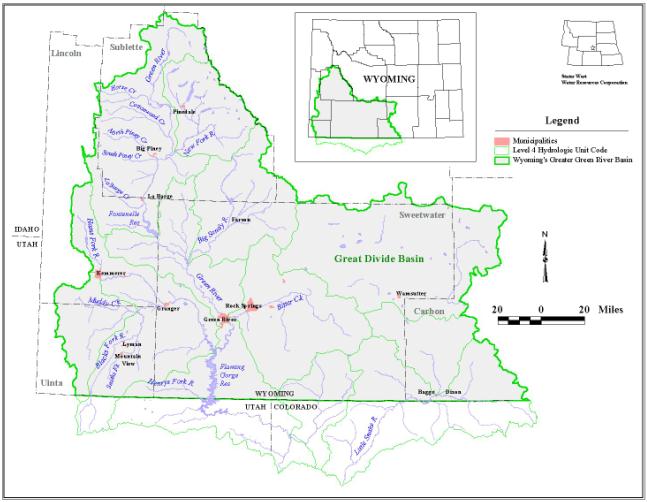

The Green River Basin consists of lands in Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah that drain to the Green River, the largest tributary of the Colorado River. The Wyoming portion of the Basin comprises nearly 25,000 square miles. It is bordered on the east by the continental divide including the Wind River Range in the north and northeast, the Great Divide Basin centrally, and the Sierra Madre Range in the southeast. It is bordered on the south by the Wyoming-Colorado and Wyoming-Utah state lines. The Basin's western border is defined by the Tunp Range, which forms the division between the Green and Bear River Basins, and the Wyoming Range, which separates the Green from the Greys River Basin. The far northwest of the Basin abuts the Gros Ventre Range. While the Green River Basin includes the Great Divide Basin for purposes of this plan, this region is a closed basin, and does not contribute any run-off to the Green River. Figure I-1 shows the study area, sometimes referred to as the Greater Green River Basin.

Figure I-1 Greater Green River Basin: Study Area

click to enlarge

Counties that contribute large areas to the Basin are Sweetwater, Sublette, Carbon, Lincoln, and Uinta, with small areas in Fremont and Teton counties. This area is just larger than the State of West Virginia.

Topography

The Basin generally slopes to the south, with major portions of the area having elevations in the range of 6,000 to 7,000 feet above sea level. This area is characterized by the buttes, mesas, and badlands associated with high, arid desert plains. Mountainous peaks that form the majority of the Basin border frequently exceed 10,000 feet in elevation in the northern and northeastern reaches of the Basin, and 9,000 feet in the southern reaches in Wasatch National Forest. The highest point in the Basin (Gannett Peak, elevation 13,804) is also the highest point in the State, and the lowest point (elevation 6,040) occurs along the Green River where it passes into Utah at Flaming Gorge Reservoir.

Climate

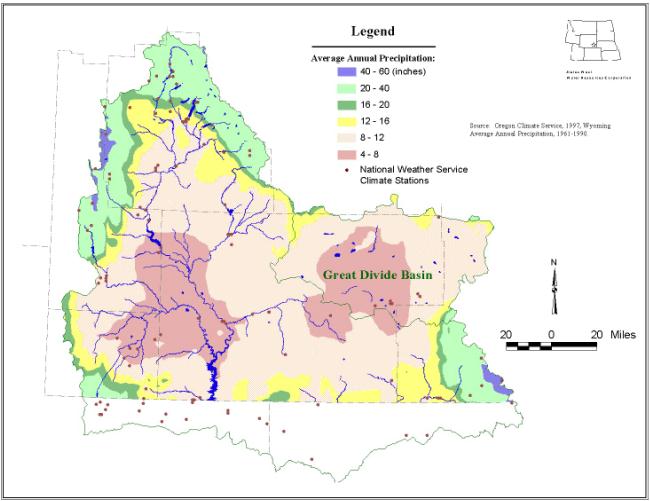

Climate throughout the Basin varies, but generally follows the pattern of a high desert region. Higher precipitation and lower temperatures generally accompany higher altitudes. Precipitation data are available for about a dozen National Weather Service stations in the Basin for the past 30 years. The lowest average annual precipitation among these stations occurs at Fontenelle Dam in Lincoln County (7 inches), and the highest average annual precipitation occurs at Pinedale (11.4 inches). Precipitation in the range of 40 to 60 inches annually, most occurring as snow, falls in the highest mountains. While long, mild intensity rainfall events do occur in the Basin, the majority of the rainfall occurs in short, intense storms. Various climatological and physiographic factors combine to create a relatively short growing season throughout the Basin. Figure I-2 shows precipitation characteristics in the Basin.

Figure I-2 Average Annual Precipitation

click to enlarge

Water Features

Most notable of the water features in the Green River Basin is the Flaming Gorge Reservoir along the Green River as it passes into Utah, and which is formed by the Flaming Gorge dam in the State of Utah. Other major bodies of water in the central and eastern part of the Basin include the Green River Lakes, New Fork Lake, Willow Lake, Fremont Lake, Halfmoon Lake, Burnt Lake, Boulder Lake, Big Sandy Reservoir, Eden Valley Reservoir, and Fontenelle Reservoir, in addition to numerous high mountain lakes in the Wind River Range. In the western part of the Basin are Viva Naughton and Kemmerer No. 1 Reservoirs. To the south, Meeks Cabin and Stateline Reservoirs serve various Wyoming users, although Stateline is located entirely in Utah.

Waterways leading to the Green River include numerous rivers and streams, many with multiple branches. Major tributaries include the New Fork, East Fork, and Big and Little Sandy Rivers in the northeast; the Little Snake River in the southeast; the Hams Fork, Blacks Fork and Henrys Fork of the Green in the southwest; and the Piney, LaBarge, Fontenelle, Cottonwood and Horse Creeks (among others) in the north and west. Many of the streams and creeks in the central and southern parts of the Basin are intermittent or ephemeral, flowing only in response to rainfall or snowmelt.

History

Although evidence of human occupation of the Green River Basin exists from 9000 BC, its modern history did not take shape until the 1800's. The first white man reported to have entered the Basin, John Colter, was a member of the Lewis and Clark expedition, although the Basin was not a part of their explorations. After returning to St. Louis with Lewis and Clark, Colter assembled an exploration party of his own and returned to the area in 1807.

In 1824, General William H. Ashley explored the area around the Sweetwater River. He gave the Green River its name; until then it was known as the Spanish River. Ashley trapped for fur throughout the Basin. In 1825, Ashley began the first of several annual trapping rendezvous on Henrys Fork. In time, this rendezvous became not only an assembly of trappers, but others (especially Native Americans) who were interested in trading. In 1826, Ashley retired, and his interests were eventually bought by the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. In the 1830's, the rendezvous was moved north to a site not far from present-day Daniel.

In May of 1832, Captain B.L.E. Bonneville led a large exploration party to the Basin. He established "Fort Nonsense" (as it was called) near the mouth of Horse Creek, not far from present-day Pinedale. Unlike other pioneers of the area, Bonneville was not really interested in furs. His fort was chiefly for the purpose of spying on British and Indian activities in the mountains. Antagonistic Indian attacks forced the almost immediate abandonment of "Fort Nonsense."

Jim Bridger, perhaps the most well-known figure in Green River Basin history, was a member of General Ashley's expedition. After Ashley's retirement, Bridger continued to trap for furs in the Basin. With the fall of the fur business and the rise in emigrant travel through Wyoming, Bridger, as with many others, refocused his business on trading with the emigrants. In 1842, he built Fort Bridger with his partner, Louis Vasquez. Fort Bridger was strategically located to serve multiple trails. There, they made a rather profitable business. In 1848, the fort officially became a part of the United States as the region was ceded from Mexico. During this same year, gold was discovered in California. Gold had been found in the South Pass area six years earlier, but the strikes had not been as fruitful as in California. During the early 1850's, emigration through the Basin flourished, leading to increased trading business. In November of 1853, a crew of Mormons established Fort Supply, a dozen miles from Fort Bridger. In 1857, both forts were destroyed as the Mormons fled government troops. Fort Bridger was eventually rebuilt and became a military fort. During the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad, it housed troops protecting railroad surveyors and construction crews.

While the Fort Bridger area developed for trading, the South Pass area came into being due to gold prospecting. Gold had been discovered in the area in 1842, and serious prospecting continued for nearly 20 years. News of the finds trickled to emigrant centers such as Fort Bridger and Salt Lake City, and numerous explorers made their way to the area. This influx of people, while considerable, was never as great as that traveling on to California and Oregon. The region was still seen as an unforgiving and hostile area. Over the years, prospecting began to take a backseat to other business ventures. Many prospectors found hay production for emigrants and production of telegraph poles to be more lucrative than gold. Interest in gold was renewed in 1867 with the discovery of the Carissa Lode. Inflated tales of gold finds spread and the area experienced a boom in population. With the discovery that these tales were misleading, many prospectors left the area within a few years. Those who stayed realized the potential for grazing and ranching throughout the northern portion of the Basin.

Communication and transportation have played major roles in the development of the southern portion of the Basin during the majority of its history. This was especially true during the 1860's. Many of the towns existing today had their roots as stage or telegraph stations. In the late 1860's, the presence of coal in the Green River/Rock Springs area was the chief factor for Union Pacific Railroad's decision to build through southern Wyoming. This created not only the demand for coal, but also the means for conveying it to other regions. A common practice of the day was for a developer to speculate upon where railroads would set-up centers of business and create towns in anticipation of future prosperity. Green River was established in such a manner in the summer of 1868. By the end of 1868, the railroad had reached as far west as Evanston. Coal had also been discovered on Hams Fork in 1868, spurring the establishment of Diamondville in 1894 and Kemmerer in 1897.

Mineral interests continued to spur the creation of new towns throughout the late 19th and into the early 20th centuries. Around 1910, the State experienced an oil boom that resulted in the establishment of the town of LaBarge in the 1920's. In 1939, trona was discovered in Sweetwater County, and, by 1952, the first mining plant had been built.

Arguably, the most valuable resource in the Basin is water. As with much of the State, having good quality water at the right times has always been a challenge. Ancient Indian civilizations were known to have constructed small canals and ditches from streams to provide crop water. With the increase in nomadic tribes, these canals and ditches were not used as extensively. The first modern use of irrigation in the Basin is credited to the Mormon settlers of Fort Supply around 1854. Emigrants and other travelers were quite impressed with the results the Mormons achieved. In 1857, when the Mormons returned to Salt Lake, the irrigation projects were temporarily abandoned. Although the first water right filings from the Blacks Fork were not completed until 1862, irrigation diversions were known to have been in place at Fort Bridger by 1859. The first water rights filings in the upper portion of the Basin occurred around 1879 on Fontenelle Creek. Gradually, irrigation of bottomlands throughout the Basin became more and more commonplace. Beginning in the 1920's, reservoir storage rights were established on lakes such as Willow Lake, Boulder Lake, and Fremont Lake.

One of the most documented and oldest reclamation projects in the Basin is the Big Sandy project. In July of 1886, an official charter was granted to the Big Sandy Colony and Canal Company to build a dam on the Sandy River. This dam was later washed away by floods and the project abandoned. In 1906, the Eden-Farson Irrigation project was authorized. By 1914, the main canal had been finished. Over the course of the next 20 years, financial instability and mismanagement plagued the project, and it eventually came under the dominion of the Bureau of Reclamation. Further improvements were authorized, but construction did not begin until 1950 due to World War II. 1950 also marked the birth of the Eden Valley Irrigation and Drainage District. During the 1950's, improvements and expansions were completed for many aspects of the original canal project. Other reclamation projects that currently exist in the Basin include the Flaming Gorge Dam, completed in 1962, Fontenelle Dam, completed in 1964, the Meeks Cabin Dam, completed in 1971, and the Stateline Dam, completed in 1979.

Although the main use of surface water within the Basin is agricultural, the various streams in the area also provide water for domestic use. Many cities (such as Rock Springs and Green River, and the towns within the Bridger Valley) have a shared point of diversion and distribution system. In many cases, the water supply facilities were built and are currently maintained by private corporations.

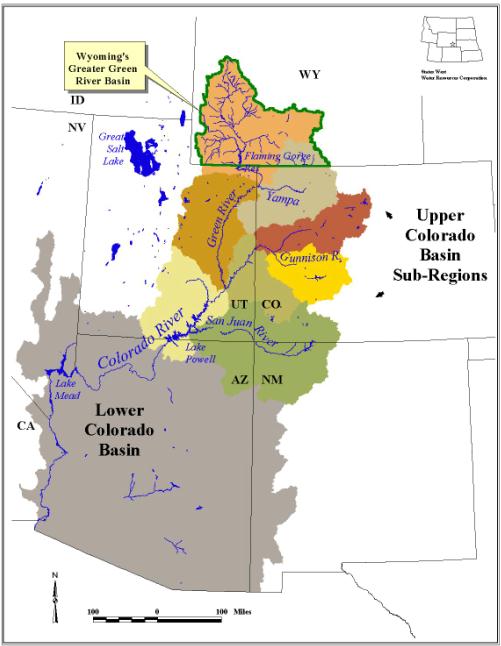

Colorado River Basin

The Green River is the largest tributary within the Colorado River Basin (Figure I-3). In addition to land in Wyoming, the Colorado River Basin drains large portions of Utah, Colorado, all of Arizona, and small portions of New Mexico, California, Nevada, and Mexico, for a total of 244,000 square miles. In accordance with the Colorado River Compact, the large basin is divided into two main divisions: the Upper Basin, consisting of the land draining to the Colorado River upstream of Lee Ferry, Arizona; and the Lower Basin, consisting of the land draining to the river south of Lee Ferry. The Basin is further subdivided into the Green Division, the Grand Division, the San Juan Division, the Little Colorado Division, the Virgin Division, the Gila Division, and the Boulder Division.

Figure I-3 Colorado River Basin

click to enlarge

One of the primary tenets established during conception of the current water planning process was that Wyoming Water Law would be respected throughout that process. That is, while many aspects of the use, availability, value and future demands of Wyoming's water would be under review, the principles of administration of that water by the State Engineer's Office would not.

As Engineer for the Territory of Wyoming, and later the first State Engineer, Elwood Mead understood that in a water short region, water must be administered in a fair and equitable fashion, and his method for doing so was to let the earlier developer have the better right to the water (the priority system). He also knew that the amount of any right must be affirmed by an agent of the State, lest the applicant greatly exaggerate the amount needed, and be based on the amount put to "beneficial use." Another stamp of Mead's early efforts in Wyoming is the resolution of water disputes via a "Board of Control," rather than the water court system used in the neighboring state of Colorado. In Wyoming, water rights are property rights in that they are attached to the land and can be transferred in use or in location only after application to and careful consideration, and possible modification, by the State Engineer if the water right is unadjudicated, otherwise by the Board of Control. The Board of Control is made up of the four water division superintendents and the State Engineer.

Water Law in the Constitution and Statutes

Water ownership and administration is defined in Article 8 of the Wyoming Constitution:

Water law is defined and codified in the Wyoming State Statutes. The State Engineer's role is defined under Title 9, Chapter 1, Article 9, (W.S. 9-1-901 through 909), along with the authority to establish fees for services. Weather modification activities are placed under the authority of the State Engineer in this Article, and moisture in the clouds and atmosphere within the state boundaries is declared property of the State.

Title 41 is entitled "Water" and contains the bulk of Wyoming's laws related to water. Under this Title the following chapters are included:

Within Title 41, Chapters 3 and 4 contain the important laws relating to establishment, administration and adjudication of water rights in Wyoming. These relate to appropriation from all sources of water, whether they be live streams, still waters and reservoirs, or underground water (ground water).

The reader is referred to the Constitution and to these statutes for the complete language defining Wyoming Water Law. The monogram: Wyoming Water Law: A Summary, by James J. Jacobs, Gordon W. Fassett and Donald J. Brosz is included in the technical memorandum Wyoming Water Law Summary, as is a glossary of water-related terms.

The Green River of Wyoming is the major tributary to the Colorado River, one of the most physically controlled and institutionally managed rivers in the world. It drains the largest river basin in the United States save the Mississippi. Prone to flooding and needed for irrigation, the river came under the control of several major dams in the 20th century. Management of these structures, of the water in the River, and the distribution of the water for various needs has resulted in a regulatory and legal framework now known as the "Law of the River." Documents comprising the Law include:

Wyoming's ability to develop and consumptively use water in the Green River Basin primarily is constrained by the two interstate Compacts, the Colorado River Compact and the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact. Complete copies are contained in the technical memorandum entitled Summary of Interstate Compacts.

The Colorado River Compact

The states of the Colorado River System include Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. By the 1920s, development of the Colorado River for irrigation had progressed more rapidly in the lower basin reaches than in the upper and the need for flood control and municipal water throughout the Basin was becoming more and more evident. Headwater states were growing nervous over development in the lower states and the concomitant threat that their own future uses could be curtailed. Because the many states each laid claim to Colorado River water within their boundaries, while the federal government asserted authority over this interstate (and, in fact, international) watercourse, some overarching agreement on the operation of the river was inevitable.

With the creation of the Colorado River Commission in January of 1922, and appointment of commissioners from the basin states and the federal government, work on the Compact began. Public hearings were held in all the affected states, and the resulting Compact was signed by each commissioner and a representative of the United States on November 24, 1922 in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Because the signatory states and the federal government each were required to ratify the Compact, the work was yet to be completed. The next year, six of the seven states (all but Arizona) ratified the Compact. Without unanimity, however, the Compact would not be binding. Legislation was passed in 1928 allowing the Compact to come into effect if six of the seven states (one of which had to be California) ratified it, and it did so. Arizona finally ratified the Compact in 1944.

The Colorado River Compact divided the Colorado River into two parts, an upper and a lower basin. The dividing point between the two is one mile below the mouth of the Paria River, at Lee Ferry, Arizona and is a natural point of demarcation. This point today is eight miles below Glen Canyon Dam. The States of the Upper Division were defined as Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming and the States of the Lower Division included Arizona, California and Nevada. Under the hydrologic assumptions of the day, and based on the relatively short period of hydrologic record, the long-term yield of the total watershed was erroneously deemed to be in the range of 16 to 17 million acre-feet annually. To split the bounty, the Compact apportioned to each the upper and lower basins a total of 7,500,00 acre-feet of beneficial consumptive use annually. Additionally, the Compact granted the lower basin the right to increase its beneficial use by 1,000,000 acre-feet annually. Further, the Compact requires that the States of the Upper Division cannot cause the flow at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate 75,000,000 acre-feet during any consecutive 10-year period. The Compact also made allowances for future treaties with Mexico. Essentially, deficiencies in meeting any forthcoming treaty obligations with Mexico were to be borne equally by the upper and lower basins.

Unfortunately, the yield of the upper basin has not proved to be as robust as the Compact represents. Different estimates have put the yield available for consumption in the upper basin from as low as 5,800,000 acre-feet per year up to at least 6,300,000 acre-feet per year, the latter of which is the current position of the upper basin states.

The Upper Colorado River Basin Compact

While the lower basin states were initially unable to agree on how to use their Compact allocation, the States of the Upper Basin were able to establish a division of the water so that development could begin. The Upper Colorado River Basin Compact, signed in October of 1948, followed the format of and was subject to the provisions of the original Colorado River Compact. This Compact among the upper basin states apportioned 50,000 acre-feet of consumptive use to Arizona (which contains a small amount of area tributary to the Colorado above the Compact point at Lee Ferry) and to the remaining states the following percentages of the total quantity available for use each year in the upper basin as provided by the 1922 Compact (after deduction of Arizona's share):

Colorado = 51.75 percent; Utah = 23.00 percent; New Mexico = 11.25 percent; Wyoming = 14.00 percent.

Taking into account the vagaries in knowledge of the actual yield of the upper basin, the likelihood that upper basin deliveries will be needed to help meet treaty obligations with Mexico, and a full 50,000 acre-foot development by Arizona, Wyoming's developable water under the two Compacts can be estimated at between 728,000 and 938,000 acre-feet per year. Using the most probable assumptions, the probable long-term available water supply for Wyoming from the Green River and its tributaries is 833,000 acre-feet per year. This number was recommended by the Wyoming State Engineer's Office, and memoranda describing its derivation are included in the Summary of Interstate Compacts Technical Memorandum.