| ||||||||||

| Home Page News & Information River Basin Plans Basin Advisory Groups Planning Products |

TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM

This memorandum discusses present environmental and recreational uses of water in the Wind/Big Horn Basin (WBHB). Environmental and recreational uses are for the most part non- consumptive uses. Environmental and recreational uses are very important in the Basin with respect to socioeconomic impacts and general contribution to Wyoming's quality of life. This memorandum contains the following sections:

Section 1 - Introduction

1. Introduction: Environmental and recreational water needs are closely related, and are often, in the current social and regulatory climate, controversial. Institutional factors play a large role in the management of water for these needs, particularly in the WBHB, where nearly eleven million acres are public land. Recreational uses of water, such as fishing and boating, are usually non- consumptive, but dedication of water to environmental purposes can at times exclude other uses. The quality and quantity of good recreational opportunities, however, are highly dependent on water quality and quantity – the two uses are closely interrelated. Recreation, including tourism, is one of Wyoming's three major industries. Hunters and anglers alone spent $700,588,360 in the state in the year 2000.1 Major recreational activities dependenton water are fishing, boating, waterfowl hunting, and swimming. Other recreational activities, such as big-game and upland game bird hunting, snowmobiling, skiing, sight-seeing, photography, camping, and golfing are also more or less sensitive to water quantity and quality. It is often difficult to gather quantitative data for specific locales in regard to recreational and environmental activities and needs, but agencies such as Wyoming's Game and Fish Department, Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources, and Business Council, as well as federal agencies such as the Forest Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Reclamation, Natural Resource Conservation Service, Bureau of Reclamation, and National Park Service gather and analyze data relevant to recreational water management. The Wind River Indian Reservation also collects some data, as do some counties and municipalities. 2. Institutional Considerations Institutional variables are very important in assessing current and future uses, both environmental and recreational. Management of land, water, wildlife and associated resources occurs within a multifaceted context of institutional constraints. Federal legislation relevant to water development includes the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the Historic Preservation Act. Executive Orders, such as EO11988 (Flood Plain Management) and 11990 (Wetlands Protection) also apply. However, perhaps the most basic institutional constraint is fragmented ownership and control of natural resources. This is the case in Wyoming in general, where about half the land is owned and managed by federal agencies, and management and ownership of the other half is divided among state, county, local, and private entities. Given that the headwaters of most Wyoming streams are located on federal lands, federal involvement in water development and management is inevitable. 2.1 Land Ownership and Management An important factor in managing lands and waters for recreational and environmental purposes is the fractured nature of land ownership and control in the WBHB. Nearly 71% of the Basin's 15.2 million acres land is publically owned, with management divided among numerous governmental agencies at local, state and national levels. National policy trends, particularly in regard to the environment and to economics, probably influence how Federal lands within the Basin are managed more than do state or local preferences. Table 1 reveals the diverse nature of land management in the WBHB. Table 1: Land Ownership in the WBHB2

Another variable that cannot be ignored is that the Wind River Indian Reservation incorporates about 2.2 million acres in Fremont and Hot Springs Counties. Demographic, economic, social and political factors within the Reservation can influence resource management in the whole of the WBHB. 2.2 Threatened, Endangered and Candidate Taxa: The presence of threatened or endangered species of plants and animals, or of species that might be considered for such listing, can make water management and development more complex. A number of taxa in Wyoming are so listed. Section 2 (c)(2) of the Endangered Species Act requires state and local agencies to cooperate with federal agencies in issues involving such taxa. Particularly in cases in which federal land is involved, such cooperation means conducting wildlife and plant studies of the targeted area. Some of the listed animal and plant taxa are found in the WBHB. Animal species listed include the grizzly bear, whooping crane, Kendall Warm Springs dace, bald eagle, black-footed ferret, lynx, Preble's meadow mouse, Pike minnow (squawfish), razorback sucker, Wyoming toad, and gray wolf. Listed plant species are Colorado butterfly plant, blowout penstemon, Ute ladies' tress, and desert yellowhead. There are also other taxa that have been proposed for addition to the Threatened list, and a long list of Candidates (258 species) for endangered or threatened status. Efforts are ongoing to protect and restore populations of the Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout in the WBHB, particularly in the drainages of the Greybull, Wood, and South Fork of the Shoshone rivers. Shovelnose Sturgeon have been released in the Big Horn River in an effort to restore those populations. In regard to threatened and endangered species, however, the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service states that "While it is prudent to take candidate taxa into account during environmental planning, neither the substantive nor procedural provisions of the Act apply to a taxon that is designated as a candidate."3 Nonetheless, as a practical matter, the presence or possible presence of Threatened, Endangered, Proposed or Candidate taxa in locales that could be affected by water projects must be considered by developers. Wildlife and plant (and cultural) studies are routinely done early on in most projects, particularly if public lands are involved. 2.3 Wild and Scenic Rivers: Wyoming's only Congressionally designated "Wild and Scenic River" is a twenty-mile stretch of the Clarks Fork River, in Park County. Other WBHB streams have been suggested as deserving protective status, including the Porcupine drainage in Big Horn County, the Middle Fork of Powder River (which heads in Washakie County but flows eastward into the Powder River Basin), and Wiggins Fork in Fremont County.4 The Clarks Fork heads in Montana's Beartooth Mountains, flows into Yellowstone Park and Park County, and then north to Montana again. The River provides wilderness-type fishing and kayaking, especially in its spectacular canyon. Fishing pressure is higher outside the Park, in the lower reaches of the River. The possibility of damming the River for purposes of storage, power generation, bringing new land under irrigation, and perhaps transferring Clarks Fork water into the Shoshone River Basin, has been investigated.5 2.4 Glaciers The Wind River Mountains are home to the largest glacier field in the lower forty-eight States. The field covers about 17 square miles, and seven of the ten largest glaciers in the lower 48 are in this field. The melt waters from these glaciers contribute to the flow of the Wind/Big Horn River, and are thought to be particularly important in maintaining fisheries and irrigation water in late summer and early fall (July through October). Total water runoff from these glaciers is estimated at approximately 56,756 acre-feet annually, about three quarters of which probably goes into the Wind River drainage, providing some eight percent of the total flow of the Wind River during the runoff period. Glacial melting is important contribution to the flows of Bull Lake Creek and Dinwoody Creek. It is estimated that up to a third of the September and October flows of these streams is of glacial origin.6 Recent observations indicate that the glaciers are receding rapidly. This recession may be due more to lack of precipitation than to climatic warming, since decadal temperature trends (since 1931) "shows no appreciable change . . ."7 Should current climatological conditions remain, Hutson suggests, it is likely that "overall stream flows would not vary significantly. The overall impact would be minimal to irrigators and other stream uses" although if drought conditions persist, they could cause "the disappearance of the glaciers within 20 years" and reduce the late summer/early fall flow of the Wind River "by approximately 8%, creating or exacerbating shortages for irrigators and in-stream flow demands." In a third scenario, a period of cool and wet years could reverse the shrinkage of the glaciers and increase the flow.8 2.5 Yellowstone National Park: Yellowstone, the nation's and the world's oldest national park, is a World Heritage Site. Although management of the Park is the province of the U. S. National Park Service, Wyoming takes the position that the Park Service needs permitting from the State to use the water. Within the portion of Yellowstone in the WBHB drainage, the Park Service has received permits from the State to drill wells for the purpose of monitoring water levels and condition, and has a surface water right to one acre-foot per year for domestic use at its East Entrance facilities. Fishing inside Yellowstone National Park does not require a Wyoming (or any state) license. Recreational and environmental management within the Park is done by the Park Service. Visitors to Yellowstone National Park provide the bulk of the WBHB's tourism. From 1990 through 2000 recreational visitors to the Park averaged nearly three million per year, but the East Entrance, west of Cody, averaged fewer than 400,000 per year during the 1992-98 period.9 The South Entrance, reached through Fremont and Teton Counties (as well as from the west and south) averaged more than 800,000 per year during the same period. These numbers suggest that perhaps 500,000 to 600,000 people bound for Yellowstone pass through the WBHB each year. The percentage who stop to recreate in the Basin is probably best suggested by sales of short-term non-resident fishing licenses. 2.6 Wind River Indian Reservation: The Wind River Reservation, home of the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Tribes, covers more than two million acres of Fremont and Hot Springs Counties. Within the boundaries of the Reservation are extensive private lands, and the Reservation operates within a context of tribal, federal, state and local authority and activity. Natural resources on the Reservation are in general jointly owned by the two Tribes. Tribal water rights date from the 1868 Treaty between the United States and the Shoshone Tribe. Water is managed under the Wind River Water Code, jointly adopted in 1991 by the Tribes.10 A Water Resources Control Board is the "primary enforcement and management agency responsible for controlling water resources on the Reservation."11 Lengthy legal proceedings between the State of Wyoming and the Tribes awarded the right to 500,000 acre-feet of water to the Tribes, of which 290,000 acre feet are reserved for future use. The Tribes sought water rights for such environmental/recreational purposes as wildlife usage or instream flows in litigation, but failed in court to receive such rights.12 Within the Reservation are more than 200 lakes and over 1000 miles of streams. Fishing on the Reservation requires a Tribal license. The Tribes reported selling 2,472 permits in 1998, and 3,577 in 1999. About sixty percent of these sales were to non-residents.13 There is significant potential for further development of recreational opportunities, including water-based activities, on the Reservation. 2.7 Reservoir-allocated Conservation Pools and Recreation Permits: In Wyoming uses of water that are recognized as beneficial uses include irrigation, municipal, industrial, power generation, recreational, stock, domestic, pollution control, instream flows, and miscellaneous. The U. S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) has designated storage for particular uses in five WBHB reservoirs: Big Horn Lake and Boysen, Buffalo Bill, Bull Lake, and Pilot Butte Reservoirs. "Conservation storage" describes all of the storage capacity allocated for beneficial purposes, and is usually divided into active and inactive areas or pools. "Active storage," or "Active Conservation Pool," refer to the reservoir space that can actually be used to store water for beneficial purposes. Each reservoir has an allocation for an Active Conservation Pool which holds reservoir inflow for such uses as irrigation, power, municipal and industrial, fish and wildlife, navigation, recreation, water quality, and other purposes. "Inactive storage" refers to water needed to increase the efficiency of hydro power production, to areas beneath the lowest outlet structures, where water can't be released by gravity, and to areas expected to fill up with sediments. Table 2 displays the size of the Conservation Pools in WBHB reservoirs, while Table 3 shows permitted water rights that include a recreational component. Table 2: WBHB Reservoir Conservation Pools (Acre-feet)

Table 3: Permitted Water Rights* in the WBHB with Recreation Component14

*Recognized beneficial uses include: irrigation, municipal, industrial, power generation, recreational, stock,domestic, pollution control, instream flows, and miscellaneous.2.8 Instream and Maintenance Flows and Bypasses: In Wyoming, Instream Flow Water Rights cannot be issued to private interests – only the State can hold them. The Wyoming Board of Control has interpreted the use of instream flows narrowly – they are for fisheries protection only.15 However, maintenance of instream flows can also benefit water quality, riparian and flood plain management, ground water recharge, and aesthetic considerations. The Wyoming Game and Fish Department has since 1994 taken action to identify streams for which the filing of applications for instream flow water rights were appropriate. The Department established criteria for instream flow segments: the stream must be an important fishery, located on public lands or lands with guaranteed public access, or have existing instream flow agreements.16 Table 4 provides data on In Stream Flow Applications in the WBHB. It is believed that most or all current applications will be approved, and applications for more streams will be filed in the near future.17 Table 4: WBHB (Water Division #3) Instream Flow Applications18

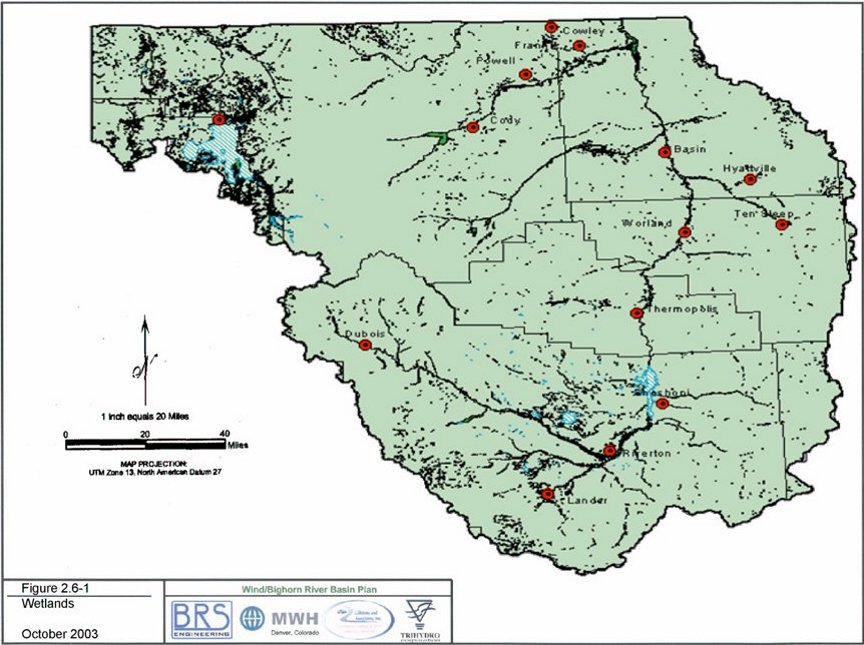

2.9 Wetlands and Riparian Areas: Riparian areas and wetlands are ecologically important, helping to maintain stream flows, reduce erosion, and provide wildlife habitat. These beneficial effects contribute to higher quality recreational opportunities also, and have beneficial impacts for livestock as well. Wetlands are classified as lacustrine, palestrine, and riverine.19 Types and acreage of wetlands are shown bycounty in Table 6. Figure 1 maps wetlands areas in the WBHB. Table 5. WBHB Wetlands (types and acreages by county)

The US Department of Agriculture has a number of programs administered by its Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) that are relevant to wildlife habitat and riparian areas. Among these initiatives are the Wildlife Habitat Incentive Program (WHIP), the Environmental Quality Incentive Program (EQIP), the Conservation Resource Program (CRP), and the Wetlands Reserve Program (WRP). WHIP works with public and private organizations to improve riparian and wetland areas, as well as in upland improvement projects.20 EQIP works with landowners on soil, water, and related concerns, and funding for the EQIP program is steadily increasine.21 In the year 2001 the EQIP program allocated $746,500 for the W/BH (Wyoming's total allocation was $2,642,900). Active projects under EQIP were ongoing in each of the Basin's five counties.22 For the WBHB Counties EQIP budgets from 2000 through 2002 were: 2000: $893,983; 2001: $1,059,000; 2002: $1,919,000 (approximate, anticipated).23 2.10 Waterbodies with Water Quality Impairments: Waters are declared "impaired" when they fail to support their designated uses after full implementation of the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System permits and "best management practices." Under the Clean Water Act, every state must update its "303(d)" list of impaired waters every two years after reviewing "all readily available data and information." Appendix A provides listing information on waterbodies in the WBHB that are considered quality impaired under section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act. 3.0 Summary of Consumptive Uses 3.1 Evaporation: In the Basin's dry climate, evaporation losses are significant, particularly from the larger reservoirs. The Wind/Big Horn River, of course, traverses the lowest portions of the basins, where warmer weather increases evaporation rates. Evaporative losses are not specifically mentioned in the Yellowstone River compact between Wyoming and Montana, but are accounted for in the gauge readings used to calculate each state's allocation.24 Refer to Technical Memorandum - Water Use From Storage, Chapter 2, Tab 10, for evaporative losses from sotage. 3.2 Direct Wildlife Consumption: There is no easy way to quantitatively estimate the amount of water required by wildlife in the WBHB. Differences in species, terrain, food sources, weather and climate are all relevant to the water needs of wildlife. Moose, for instance, are far more dependant on riparian areas than are pronghorns. Waterfowl and upland game birds have differing needs. The more moisture in the feed sources, the less water most wildlife consume directly. In times of drought, most herbivores require more drinking water. Tyrell, in a review of the topic in the Green River Basin plan, noted that estimates of wildlife use of surface water in that Basin ranged from 100 to 400 acre-feet per year. Tyrell concluded that "while some uncertainty exists in the exact consumption value, its probable magnitude is not so high as to materially affect the water plan."25 This conclusion seems reasonable, since beef cattle, on average, consume something like 8 to 10 gallons of water per day, and sheep about one gallon.26 The consumptive water needs of wildlife would be much lower than those of domestic livestock. If, in the case of the WBHB we double the estimated amount of water consumed by wildlife in the Green River Basin, it would be 200 to 800 acre feet – still not a large amount. It seems likely that if Tyrell's conclusion errs, it is on the high side. If there were 250,000 animals in the WBHB each drinking a gallon a day the total consumption would only be .76 acre- feet per day, or 280 acre-feet per year. Distribution of water on ranges is probably a more significant problem than quantity. Forage is not as fully utilized by livestock or wildlife when it is too far from water. 4.0 Recreational Demands: Water is important in both outdoor and indoor recreation. Although in terms of volume the water demand for "indoor" (in the present context meaning such facilities as swimming pools and water parks) is not high, such facilities are significant socially, and can be economic assets. School, municipal, private and commercial swimming facilities exist in most of the Basin's larger towns. The water demand of such facilities is for the most part captured as part of municipal water demand. Outdoor recreation is an integral part of the Basin's culture. The larger reservoirs in particular, Buffalo Bill, Boysen, and Big Horn, are major water-based recreation destinations. Fishing, boating, and picnicking are popular pastimes at these reservoirs. The drainages of the Shoshone, the Clark's Fork, the upper Wind, and the Big Horn all attract anglers, as do many reaches of the rivers themselves. Rafting and boating is carried on in all the rivers, with kayaking and whitewater rafting available in canyon reaches of the rivers. Water is an important amenity in all the state parks in the Basin. In addition to public waters, there are a few small private fishing reservoirs. There are about 95 river miles along the Wind/Big Horn River from Boysen Dam to Big Horn Canyon. A 1986 Bureau of Land Management (BLM) report, prepared with the cooperation of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, estimated that most recreationists on this reach of the river were residents, with heavy use areas receiving around 1200 visitor days per year, medium use areas averaging perhaps 600 to 800 user days, and low use areas fewer than 500. The heavier use areas were mostly around the larger towns situated on the River – Thermopolis, Worland, Basin, Greybull and Lovell. Water quality is best through the southern reach of the river, near Thermopolis. In this vicinity the stream is fairly rapid, seldom freezes over, the water is usually clear, and there are good populations of fish and waterfowl. The BLM report noted that on the River there are limited opportunities for river recreation and flatboating.27 There appears to have been no major change in these patterns. 4.1 State Parks: There are five state parks in the Basin: Medicine Lodge in Big Horn County, Hot Springs in Hot Springs County, Sinks Canyon and Boysen in Fremont County, and Buffalo Bill in Park County. The Basin's State Parks are estimated to attract more than a million visitor-days per year.28 Water is an attraction at all of these parks. Boysen and Buffalo Bill are located at large reservoirs, Hot Springs (which hosts the most visitors) and Sinks Canyon State Parks are located at unique water resources, and Medicine Lodge Creek adds significantly to the attractiveness of its namesake park. In addition to the State Parks, there is a state-designated historical site, at Legend Rock in Hot Springs County. 4.2 Fishing: Fishing is probably the Basin's major water-based outdoor recreational activity, although pleasure boating and waterfowl hunting are popular also. The major source of data collected on fishing is the Wyoming Game and Fish Department's license sales and creel censuses, but these data provide only a rough indication of fishing pressure. The available quantitative data on fishing are not readily adaptable to individual waters because angler surveys are usually conducted on major waters, in response to specific needs.29 In the year 2000, 20,942 resident and 30,372 non-resident licenses were sold in the five counties of the WHBH.30 A comparison of fishing license sales in 1995 and 2000 indicates that during that period resident license sales dropped by about 8% in the Basin as a whole, while non- resident sales increased by about 20%. There were about 25% more non-resident licenses than resident sold in 2000. This is a notable change from 1995, when the difference was less than 10%. Only about 5% of non-resident licenses sold are annual permits, however. Again, sales of Wyoming fishing licenses in 2001 declined by more than eight percent compared to sales in 2000.31 It seem clear that fewer than half of the Basin's residents fish. The majority of fishing licenses sold in the Basin, both resident and non-resident, are sold in Fremont and Park Counties.32 This suggests that the drainages of the upper Wind and the Shoshone see the heaviest stream fishing pressure. The Clark's Fork is another important fishery, and there are many popular streams and mountain lakes on the west side of the Big Horn Mountains. Boysen and Buffalo Bill Reservoirs are particularly popular fishing venues. Wind River Canyon itself is on the Reservation, and both state and reservation licenses are required. Fishing pressure in the canyon is probably decreased by this requirement, but the stretch remains a fairly popular venue. Several miles of the Big Horn River below (north) of Wind River Canyon, in the Thermopolis area, provide good fishing also. Among the reservoirs, Boysen and Buffalo Bill are particularly important fisheries. Other important reservoirs for fishing (and other water sports) are Deaver Reservoir, Lake Cameahwait, Newton Lakes, Ocean Lake, and Pilot Butte and Ralston Reservoirs. Many of the fishing streams are in the mountains, on the National Forests (Bighorn and Shoshone), or in Yellowstone National Park. Fishing pressure varies with ease of access, and high mountain lakes and streams are quite fragile ecologically. Both the National Forests include sizable wilderness areas. The WGFD manages wildlife and fisheries on the National Forests, but not in the National Park. About half of each National Forest is within the Wind/Big Horn drainage. The Wyoming Game and Fish Department (WGFD) manages fisheries with the objectives of providing angling diversity, sustaining enough catchable fish, and establishing and maintaining areas which boast trophy fish, wild fish, and unique fish. Threats to fisheries include habitat losses due to erosion (both natural and man-made), inadequate instream flow, barriers to fish migration and spawning (such as dams and dewatered channels) fish losses due to diversions or non-point pollution, and competition to native species from non-native species or algae with produce oxygen deficits. The WGFD has established a "walk-in-fishing" program to enable public access to waters surrounded by private lands. Landowners cooperate with the Department to allow such access. There are 20 such areas below (north of) Boysen Reservoir. This program provides access points to fishing on the Big Horn, Greybull, and Shoshone Rivers, and Nowood and Paintrock Creeks. In the Wind River area the Department has not been as successful in securing walk-in access, although it has secured a half-mile fishing easement near Dubois.33 Anticipating continuing growth in demand for stream fishing venues, the WGFD notes that ensuring an adequate supply of good fishing spots "is dependent on maintaining adequate stream flows in existing good segments and restoring stream flows in streams that have the potential to support good recreational fisheries."34 An available opportunity for public input in fisheries management and development lies in helping to identify potential fisheries, and suggesting ways to improve or maintain them.35 Opportunities to maintain adequate water flows to support all uses, wildlife and human, do exist. Cooperative water use agreements can often be worked out, and conservation of water may enable stream flows in some segments to be maintained or even increased. 4.3 Waterfowl: Wyoming straddles two migratory waterfowl flyways, the Pacific (west of the Continental Divide) and the Central. All of the WBHB is east of the Divide, within the Central flyway. Hunting of migratory waterfowl is largely controlled by guidelines issued by the US Fish & Wildlife Service. The WBHB is divided by the WGFD into two waterfowl management areas. The Wind River Basin (essentially Fremont County) is area 4C, while the Big Horn River Basin (the other four counties) is designated 4A. The vast majority of waterfowl hunting in Wyoming is for ducks and geese, although coot, snipe, rail and sandhill crane are also hunted, but in the W/BH Basin ducks and geese account for nearly all the waterfowl harvest. While data on specific locations are unavailable, the Game and Fish Department estimated that in 2000 WBHB Basin duck hunter days totaled 13,395, with a harvest of 19,333 ducks [Ibid., Table 5]. The WBHB is second only to the North Platte drainage in volume of duck hunting in Wyoming. Goose hunter-days in the W/BH Basin were estimated to be 7,730, with a harvest of 5,331 birds. The heaviest duck and goose hunting occurs after the middle of November, extending into early February for geese. Ducks Unlimited, which has over 4,000 members in Wyoming, reports that during the 1999-2000 hunting season 11,062 federal duck stamps were sold in the state. The WGFD reports that in the year 2000 a total of 36,208 bird licenses were sold in the state. From 1995 through 2000 an average of 24,647 geese and 54,187 ducks were harvested per year. License sales for both resident and non-resident bird licenses have increased sharply over the past five years, and the harvest trend is upward.36 Maintenance and improvement of existing wetlands and riparian areas, and establishment of new ones will be helpful in maintaining and improving habitat for waterfowl. This is a good example of the interrelationship of recreational and environmental considerations. Agricultural cropping patterns are also a factor in waterfowl populations. 4.4 Adequacy of Present Recreational Resources: It seems likely that most WBHB recreational resources are lightly used relative to national standards. The trend in resident fishing permit sales in the WBHB has been slightly down, which might be expected given the aging of the population and the out-migration of many younger Wyomingites. There seems at the same time to be a trend toward higher sales of non-resident licenses, although only about five percent of these are annual permits.37 However, the WGFD "anticipates continuing increases in demand for stream and river angling," and notes that satisfying this demand "is dependent on maintaining adequate stream flows in existing good segments and restoring stream flows in streams that have the potential to support good recreational fisheries." The Department notes that public help in identifying where these segments are or might be and hints on how such waters might be better managed "is an important opportunity for participants in the water planning process."38 Other strategies that can be useful in increasing the supply of fishing opportunities in the WBHB are designated "catch and release" areas, increased planting of catchable fish and/or fry, and manipulation of size limits and catch limits. A number of projects to diversify and add to water-based recreational opportunities have been suggested. Among them are improved signage to identify waterbodies, improved access for users, provision of more handicap access, and development and promotion of eco-tourism at water-based recreation areas. Whitewater recreation parks might be established as well. Boating and skiing, of course, are also water-based activities, as are snowmobiling, sled dogging, skijoring, and the like. There is potential to increase the number of venues and of participants in such activities.39 Most of these activities, of course, are non-consumptive. However, funding mechanisms and project sponsors are not clear. Other projects can be designed to provide recreational opportunities as multiple-use components.

Endnotes

Figure 1: Wetlands in the Wind River/ Bighorn Basin Area 1:24,000-scale

APPENDIX A Table 4A. 303(d) Waterbodies with Water Quality Impairments, 2002

Table 4B: 303(d) Waterbodies with NPDES Discharge Permits containing WLAs Expiring

Table 4C: 303(d) Waterbodies with Water Quality Threats

Table 4D: Waterbodies Delisted from 2000 303(d) List

|