Wyoming State Water Plan

Wyoming State Water Plan

Wyoming Water Development Office

6920 Yellowtail Rd

Cheyenne, WY 82002

Phone: 307-777-7626

Wyoming Water Development Office

6920 Yellowtail Rd

Cheyenne, WY 82002

Phone: 307-777-7626

V. FUTURE WATER USE OPPORTUNITIES

A. INTRODUCTION

This section discusses the procedures used to create a list of potential future projects that would utilize the water resources in the Snake/Salt River basin. This list represents the needs and desires of those in the basin, and provides a starting point for additional beneficial uses of water in the future. A long list of potential projects was first developed with input from the Basin Advisory Group (BAG). This list was then reduced and evaluated with respect to various criteria, resulting in a short list of potential projects which can be compared to one another within a given use category.

B. LONG LIST OF FUTURE WATER USE OPPORTUNITIES

The long list of future water use opportunities was created at the BAG meeting held in Moran on August 14, 2002. At this meeting, input was collected from various BAG members as well as others in attendance. Any and all input was welcome, and a wide variety of issues was discussed while adding items to the list, including past studies. The long list put together at that meeting ended up with projects for uses such as irrigation, hydropower, wetlands, water storage, recreation, and others.

While input during the BAG meeting was exceptional, there were many BAG members who were not in attendance. It was determined that the resulting long list should be distributed to the entire Basin Advisory Group in order to give everyone a chance to comment. The list was distributed via email on August 26, 2002, with a request for each BAG member to review the items and provide any input they wished. Some additional input was received following the email distribution.

C. SHORT LIST OF FUTURE WATER USE OPPORTUNITIES

Following the creation of the long list and collection of BAG member input, the resulting list was reviewed in order to reduce the list to a collection of potential water use projects. Some items on the long list, while they may be worthy of further discussion in other circles, did not warrant further investigation as part of this basin plan. This was generally for items that could only be addressed by specific state agencies, and included reciprocal fishing licenses between Idaho and Wyoming and septic tank management. The item regarding support of local conservation district projects was dropped, as there was not a specific project to be included at this time. Also, projects that appeared to have a low probability of support or feasibility were dropped, which included beaver management, terracing at high elevations, and trans-basin water diversions.

The short list of future water use opportunities consists of the remaining projects from the long list. The short list projects were then reviewed by the basin planning team and evaluated based on the short list criteria.

Short List Criteria:

A list of criteria used to evaluate the short list was created as part of this basin plan. Similar criteria have been used on all of the previous basin plans, although some changes were made to better fit the situation in the Snake/Salt River basin. For example, political acceptance was looked at in addition to public acceptance, and environmental constraints were reviewed due to the large amount of federal land and the constraints placed on those lands through environmental laws. Also, a criteria regarding multiple use was added.

The following criteria were used to evaluate the short list of future water use opportunities. Each item was scored on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being not feasible and 10 being very feasible.

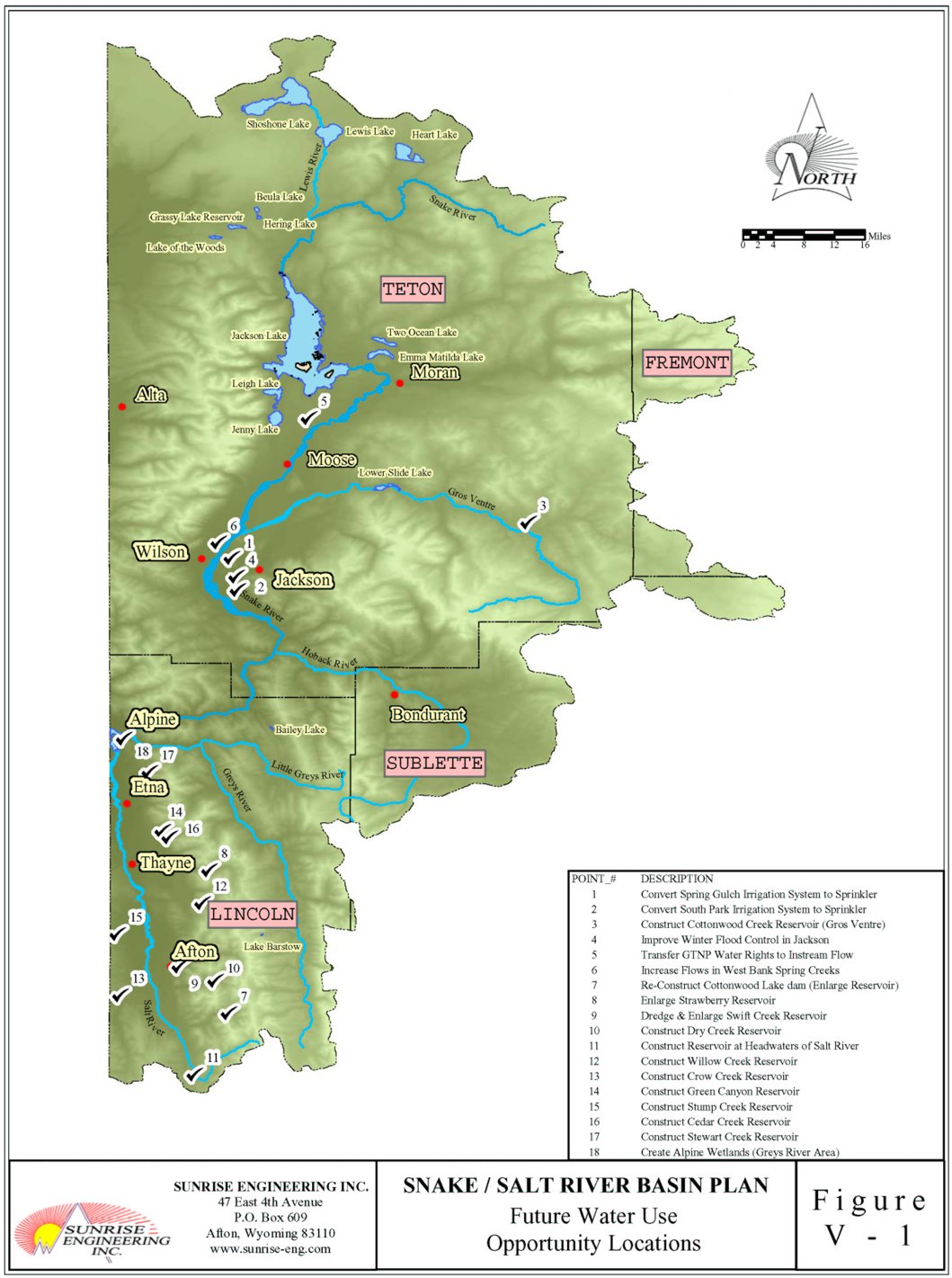

Evaluation of each project on the short list using the above described criteria resulted in a final number or score. It must be emphasized that the projects were evaluated with respect to other like projects. For example, an agricultural project regarding irrigation was not compared to an environmental project regarding wetlands. Also, the Short List was broken into sub-basins, as issues that can effect the evaluation of a project in the Snake River basin will be different than those in the Salt River basin. The results of this evaluation are located in Tables V-1 and V-2. Figure V-1 outlines the locations of these future water use opportunities across the basin. It must be mentioned that evaluation of the Short List is very subjective, and evaluation by those with various backgrounds would likely produce a variety of results.

Table V-1. Snake River Sub-Basin Short List Selection Critiera

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table V-2 Salt River Sub-Basin Short List Selection Criteria

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

D. LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL CONSTRAINTS

In recent years, federal and state laws, rules, regulations and policies have effected the business of water development and management. The purpose of this section is to identify and discuss some of these institutional constraints on the development and use of water and review how they relate to issues in the Snake/Salt River basin.

Federal Environmental Laws:

In the late 1960's and early 1970's, Congress passed legislation to protect the environment. Prior to the passage of these laws, most water projects were designed and operated for specific consumptive uses for municipal, agricultural or industrial purposes or to provide flood control or recreation benefits. Any environmental benefits derived from the projects were indirect and incidental to the purposes for which they were designed. While such benefits could be considerable, they were not protected or required by law. With the passage of environmental laws, a variety of environmental protection and mitigation actions became a "standard" consideration in the development of water projects as well as for many other types of projects. These considerations often included minimum streamflow releases and mitigation for impacted wetlands as requirements of federal approvals or permits for a particular project. At the same time, the economic and environmental benefits of recreation, fisheries, wetlands and other habitats were documented and became more apparent to the public and developers alike, which resulted in minimum reservoir pools or streamflows often becoming a planned component of reservoir operations.

Water supply development projects often require "a federal action" that initiate or trigger the federal environmental law reviews and permitting. These actions or where there is a "federal nexus" include, but are not necessarily limited to, the following:

The only water development activity that is not subject to federal environmental laws is drilling a well with non-federal funds on non-federal lands outside the banks of rivers, streams, and wetlands. However, piping the water from such wells across federal lands or rivers, streams, and wetlands could initiate a federal environmental review and a federal permitting or approval action.

Endangered Species Act

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA) declares the intent of Congress to conserve threatened and endangered species and the ecosystems on which they depend. This law requires all federal agencies, in consultation with the Secretary of Interior, through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), or the Secretary of Commerce, through the National Marine and Fishery Service (NMFS) to use their authorities in the furtherance of ESA purposes by carrying out programs for the conservation of species and by taking such actions necessary to insure any action authorized, funded, or carried out by the agency is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of such threatened or endangered species or result on the destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat of such species as determined by USFWS or NMFS. These agencies will make a biological determination as to whether wildlife and plant species are endangered or threatened based on the best available scientific information.

The current list of species maintained by the FWS for areas in or near the Snake/Salt River Basin (Lincoln, Sublette and Teton Counties) within Wyoming includes the:

| • Bald Eagle | Threatened (proposed for de-listing) |

| • Black-Footed Ferret | Experimental, prairie dog towns |

| • Canada Lynx | Threatened |

| • Gray Wolf | Experimental, non-essential population |

| • Grizzly Bear | Threatened |

| • Mountain Plover | Proposed for listing, grasslands |

| • Ute ladies'-tresses | Threatened, possible statewide in habitat below 6,500 feet |

In addition, a separate technical memorandum for this basin plan discusses the listed endangered salmon and steelhead anadromous fish species in the river downstream from Wyoming's border that can potentially affect or limit the use of water within Wyoming. All of these species are covered by the various provisions of ESA and must be considered in the development of most any water related project.

National Environmental Policy Act

NEPA requires all agencies of the Federal government to insure that presently unquantified environmental amenities and values be given appropriate consideration in decision making along with economic and technical considerations. The Act requires that federal agencies consider all reasonably foreseeable environmental consequences of their proposed actions. The conclusions of the environmental review of that action under NEPA can be in the form of (listed in order of increasing complexity, cost and time); 1) a categorical exclusion, where there are no impacts or when an action has been analyzed and documented through other NEPA planning processes, 2) the preparation of an environmental assessment (EA), which sometimes will result in a finding of no significant impact (FONSI) often summarized in a letter from the action agency, or where the documented impacts in an EA cannot be mitigated, 3) the preparation of an environmental impact statement (EIS). The EIS process is used on large, complex and controversial projects or for those projects where significant environmental impacts are identified and documented. Further, NEPA requires federal decision makers to "study, develop, and describe appropriate alternatives to recommended courses of action in any proposal which involves unresolved conflicts concerning alternative uses of available resources." (42 USC 4321 et seq., Sec. 102 (2) E).

Clean Water Act

Section 404 of the Clean Water Act of 1972 (CWA) prohibits discharging dredged or fill materials into waters of the United States without a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE). The waters of the United States include rivers and streams and initially, as of 1975, wetlands. Specific references to isolated wetlands were addressed in 1984 and there continues to be litigation surrounding the extent of regulation on wetlands, which are most often evaluated on a case-by-case basis. COE policy requires applicants for 404 permits to avoid impacts to waters of the U.S. to the extent practicable, then minimize the remaining impacts, and finally, take measures to mitigate unavoidable impacts.

Section 401 of the CWA requires that any applicant for a federal license or permit to conduct any activity including … construction or operation of facilities, which may result in any discharge into the navigable waters … shall provide the licensing or permitting agency a certification from the State in which the discharge originates that the discharge shall comply with state water quality standards. In Wyoming, the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) handles the Section 401 certification program as well as implementing CWA Sections 303(d), 305(b) and 319. Section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act requires the State of Wyoming to identify water bodies that do not meet uses, as designated by stream classifications, and are not expected to meet water quality standards after application of technology-based controls. This aspect of the law is also intended to identify a priority ranking for each water quality limited stream segment and develop total maximum daily loads (TMDL) to restore each water body segment. TMDL is the ability of a water body to assimilate pollution and continue to meet the use designated by the stream classifications. Future water development projects will need to address water quality benefits and impacts.

Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act

FWCA authorizes the Secretary of Agriculture and Commerce to provide assistance to and cooperate with federal and state agencies to protect, rear, stock, and increase the supply of game and fur-bearing animals, as well as to study the effects of domestic sewage, trade wastes, and other polluting substances on wildlife. The Act also directs the Bureau of Fisheries to use impounded waters for fish-culture stations and migratory-bird resting and nesting areas and requires consultation with the Bureau of Fisheries prior to the construction of any new dams to provide for fish migration. In addition, this Act authorizes the preparation of plans to protect wildlife resources, the completion of wildlife surveys on public lands, and the acceptance by the federal agencies of funds or lands for related purposes provided that land donations receive the consent of the State in which they are located.

National Historic Preservation Act

Congress established the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (NHPA) and created the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation to advise the President and Congress in matters involving historic preservation. The council is authorized to review and comment on activities licensed by the federal government which will have an effect upon properties listed in the National Register of Historic Places or eligible for such listing. Section 106 of the NHPA provides for the involvement of the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) in the cultural resource inventory and project reviews administered by the Council under this Act. These reviews provide for the balancing the needs of development against the need to retain significant pieces of the nations past. In Wyoming, SHPO completed over 3,000 project reviews and requests for assistance from consultants preparing the inventories and possible project impacts and mitigation actions. Water related projects would routinely be required to address the provisions of Section 106 of NHPA.

Federal Lands:

There are federal lands throughout the Snake/Salt River Basin. There are very few lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management, however the far majority of the basin land area is in the Bridger-Teton and Targhee National Forests as well as Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks. There are also designated wilderness areas within national forests, the National Elk Refuge, and candidates for wild and scenic river designations. The USFS, NPS, and BLM or others agencies managing these federal lands must assure that the requirements of federal law are met before they can issue a special use or other permits authorizing a proposed action on federal lands, such as construction of a water project.

If possible, project proponents should avoid locating their project on national forests and national parks because of the significant encumbrances that may be placed on their investments or projects. It is virtually impossible to locate new water projects within wilderness areas, wildlife refuges, and stream areas with wild and scenic river designations.

Wyoming Environmental Quality Laws:

The Section 401 of the Clean Water Act provides for the state certification of any federally licensed or permitted facility, which may result in a discharge to the water of the state. In Wyoming, this certification process is administered by the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ).

Those items typically required in the provisions of a Section 401 certifications are outlined below:

A Section 401 certification also outlines those additional permits required prior to the initiation of project construction activities. These additional permits are described below:

1. NPDES - National Pollution Discharge Elimination System Permit.

Typically, the selected construction contractor for the project will prepare and submit a "Notice of Intent" 30 days prior to any surface disturbances taking place, to DEQ. The major requirements of the NPDES (a storm water general permit) pertain to the development and implementation of a water pollution plan along with regular inspection of pollution control facilities in place at the project construction site.

2. Non-Storm Water Discharges.

An individual NPDES discharge permit from the DEQ may be required for point source discharges to surface waters not related to storm water runoff. These can include discharges from gravel crushing and washing operations, an on-stream cofferdam dewatering discharge, vehicle or machinery washing, or other material and equipment processing operations, if they are a part of the project being authorized.

3. SPCC (Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasures Permit)

If above ground storage of petroleum products exceeds 1,320 gallons in total or more than 660 gallons in a single tank an SPCC plan may have to be developed for submittal to DEQ as described in the EPA's Oil Pollution Prevention regulations.

Wyoming Water Law:

The priority date for a project is established on the date a completed water right permit application for the project is accepted by the Wyoming State Engineer's Office. In order to determine the water supply a new project may achieve, it is important to evaluate the existing water rights that are "senior" to the proposed project. Before the decision is made to pursue a project at a particular location, the potential water yield of the project should be estimated. The firm yield is the water supply benefits the project proponent could expect under worst case or drought water supply conditions. If the proposed project is located on a stream or river that has many "senior" priority water rights, a new project may not be able to achieve a reliable water supply during the drier months, such as July and August, or during drought years. Under these conditions, often the development of water storage reservoirs may be required to store water when flows are surplus to existing water rights and carry them over through the drier periods.

Generally the old "rules of thumb" relating to water yield and project feasibility were as follows:

However, today, all water users are interested in a firm water supply before they are willing to invest in a water project due to the ever escalating permitting, mitigation and project construction costs and the implementation time involved. In fact, many industrial water users are interested in the yield of a potential project under doomsday type of drought conditions, such as assuming that the worst water year of record occurs in consecutive years. These expectations of water users make the priority date of the water rights of new projects located in tight water supply regions relative to existing water rights, a critical factor in the feasibility of proposed water development projects.

Interstate Compacts and Court Decrees:

Prior to issuing any new water right the State Engineer's Office will make sure there is not any affect upon or that the use of water authorized by the permit is within the interstate compact or court decree governing the water allocations of the State of Wyoming. Article III A of the Snake River Compact provides that; "the waters of the Snake River, exclusive of established Wyoming rights (pre July 1, 1949) … are hereby allocated to each State for storage or direct diversion as follows: 4% to Wyoming and 96% to Idaho…" Any new water rights approved by the State Engineer shall be a part of this allocation. To date, it is estimated that less than one-half of this entitlement has been used within the Snake/Salt River Basin of Wyoming.

The protections provided by interstate compacts and court decrees sometimes has caused people to question the necessity for development under the principle of "use it or lose it". Compacts and Decrees provide a reliable and sound legal defense of the state's entitlements and Wyoming would use these defenses in the face of any legal challenge against unused allocations. Further, Article X of the Snake River Compact specifically addresses this issue by stating; "The failure of either State to use the waters … allocated to it under the terms of this compact, shall not constitute a relinquishment … forfeiture or abandonment of the right to such use". However, it is also good business for Wyoming to be a good steward of its compact entitlements through planning for future beneficial water use.

Wyoming Water Development Program:

Planning, constructing, and implementing a water project is costly. Adding the costs to acquire state and federal permits can be overwhelming for many small public and private entities in Wyoming. In 1975, in recognition that water development was becoming more difficult and additional water development was necessary to meet the economic and environmental goals and objectives of the state, the Wyoming Legislature authorized the Wyoming Water Development Program and defined the program in W.S. 41-2-112(a), which states:

"The Wyoming water development program is established to foster, promote, and encourage the optimal development of the state's human, industrial, mineral, agricultural, water and recreation resources. The program shall provide through the commission, procedures and policies for the planning, selection, financing, construction, acquisition and operation of projects and facilities for the conservation, storage, distribution and use of water, necessary in the public interest to develop and preserve Wyoming's water and related land resources. The program shall encourage development of water facilities for irrigation, for reduction of flood damage, for abatement of pollution, for preservation and development of fish and wildlife resources [and] for protection and improvement of public lands and shall help make available the water of this state for all beneficial uses, including but not limited to municipal, domestic, agricultural, industrial, instream flows, hydroelectric power and recreational purposes, conservation of land resources and protection of the health, safety and general welfare of the people of the State of Wyoming."

The task of setting priorities under the above all-encompassing definition falls to the Wyoming Water Development Commission (WWDC), which was also authorized by the Wyoming Legislature. The WWDC is made up of ten (10) Wyoming citizens, appointed by the Governor. The director and staff of the Wyoming Water Development Office administer the Wyoming Water Development Program.

The Wyoming Water Development Commission can invest in water projects as state investments or can provide loans and grants to public entities (municipalities, irrigation districts and special districts) for the construction of projects specific to their water needs. The WWDC has adopted operating criteria to serve as a general framework for the development of program/ project recommendations and generation of information. Individuals and project entities interested in the development of specific water projects should seek information regarding the Wyoming Water Development Program and the possibility of obtaining financial and technical assistance for the development of those projects.

Conclusions:

Water development in the 21st century is often difficult and costly. However, if a project proponent has a need for water, patience, and adequate financial resources, the federal environmental review and permitting processes can be successfully completed and permits obtained for construction of water projects. In the Snake/Salt River basin the extensive amount of federal lands and particularly the national parks and forests act as a practical limitation on extensive water development in the basin. However, carefully sized and smartly located water development projects to meet the needs of the basin citizens are institutionally possible.

The publication of the "Snake/Salt River Basin Plan" should foster discussion among water users and state officials relative to water development and conservation in the Snake/Salt River basin in Wyoming. The plan concludes that Wyoming has water to develop in the basin. The water can be used for future municipal growth, agricultural and recreational demands and environmental benefits. The Wyoming Water Development Program can invest in water projects as state investments or can provide loans and grants to public entities, such as irrigation or conservation districts, for the construction of projects.